(For Part One of this essay, click here.)

Of all orbits, the geostationary are the most valuable, with the rest of the geosynchronous orbits running a close second. Across the 21st century, they had thus become quite crowded. For obvious reasons, they were particularly ideal for surveillance; accordingly, each superpower placed numerous satellites above the homeland of the other. Satellites deployed into “the geo” had other uses as well; they could serve as weapons-platforms against those in other orbits, and played an important role in communications networks.

Yet geo orbits presented planners with a complication that gradually became evident as the number of vehicles overhead increased in tandem with rising international tension set in motion by the Second Cold War. For such satellites were especially vulnerable to the ever-present possibility that an apparently harmless communications satellite would be utilized as a space-mine. A single nuclear blast could thus damage or disrupt adjacent enemy assets, provided the aggressive power was willing to trade off the loss of his own in the vicinity. (And, while less dramatic than nukes, a point-blank strike with space-to-space missiles or a KE kill vehicle was also an option.)

Nor was this problem limited to one of deception, since it was inevitable that both powers would place overt weapons above each other’s homelands. While this could be accepted as inevitable in the continually shifting satellite configurations that characterized the lower orbits, it was quite clear that a plethora of Eurasian and U.S. weapons permanently parked adjacent to each other in the most strategic orbit of all was inherently destabilizing. The most serious pre-Zurich incident between the superpowers—that of the Mauritian stand-off—thus paradoxically resulted in decreased tensions, once each side had moved to neutralize all potentially hostile geosynchronous/geostationary satellites above its own territory. But, with the polarization of geosynchronous “territory”, the ability of each side to defend its geosynchronous position in depth—and the premium placed on a side’s ability to penetrate the other’s—became critically important.

At the time of Marshal Olenkov’s death, the poster-child of this development was the PanAsian command-satellite Roaming Tundra. A colossus hardened against both EMP blast and directed energy weapons, itself bristling with firepower, this craft was believed by U.S. intelligence to house key space-based Eurasian battle management computers, as well as a cadre of Russian and Chinese commanders. A whole grid of defense networks surrounded it, including directed-energy platforms, hunter-killer satellites and minefields of tiny micro-satellites. The U.S. geo featured a similar arrangement, centered upon three smaller stations.

But when it came to the lower orbits, matters were far more ambiguous. Planners experienced considerable difficulty formulating a set of general principles that might address how combat was likely to unfold across these regions. And with good reason. A myriad different orbital levels and inclinations (including those that led across the poles) meant that thousands of satellites were continually changing position relative to each other. Of course, the position of any one satellite was entirely predictable—unless one of them fired motors to change its orbit.

Such motors were rarely ignited, however. Not only were the precise maneuvering capabilities of any given battle-sat a closely guarded secret but, also, a maneuver for any purpose other than the correction of orbital decay tended to make everyone nervous. And (needless to say) everyone was nervous enough already, for sweeping above their heads was a dizzying array of military hardware: full-scale SkyMechs, smaller directed energy platforms, mirror satellites to reflect both space-based and ground-based lasers toward their target, kinetic energy kill vehicles, manned space-stations of every size and description, and devices that added to the general tension by virtue of their purpose being not entirely clear. It seemed likely that conflict here would be as chaotic as the disposition of forces; studying the issue, generals exhaled deeply and braced themselves for the mother of all free-for-alls.

NEXT: THE MOON AND THE LIBRATION POINTS

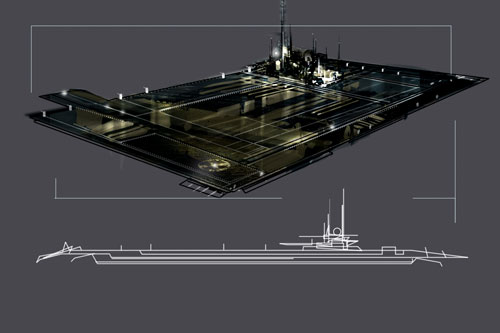

In the eyes of their designers, two factors made the Rafts a survivable proposition: first, most of their weapons could be utilized for defensive purposes against oncoming missiles (e.g., the craft possessed a myriad smaller lasers that could be trained directly upon such incoming targets) and, second, a Raft was so large that even a direct hit was unlikely to be fatal. When possible, Rafts were placed on or near the equator to maximize their space-launch potential.

In the eyes of their designers, two factors made the Rafts a survivable proposition: first, most of their weapons could be utilized for defensive purposes against oncoming missiles (e.g., the craft possessed a myriad smaller lasers that could be trained directly upon such incoming targets) and, second, a Raft was so large that even a direct hit was unlikely to be fatal. When possible, Rafts were placed on or near the equator to maximize their space-launch potential.